Handkerchief

My father had a sneeze that would wake the dead.

You could hear it from a quarter mile away on a clear day, and if you happened to be indoors in the same room–say, church or a crowded restaurant–people jumped, waiters startled, and small children clung to their mama’s necks at the sound. He used to joke that he tried to keep it in once, but it blew his eyeballs out, which was what enabled him to do his favorite dad illusion of popping an eye out, swishing it around in his mouth and popping it back in, a feat that equally fascinated and horrified his grandchildren. “Do it again!” they’d cry, trying to ferret out the trick.

He was liberal with the black pepper, which would reliably get him going with at least three or four deafening AAAA-chooo!!’s in a row. Alert family members could see it coming, like the slight tremors before a richter-scale quake. He’d pat his pockets, tilting in his seat for better reach, remove his glasses, and finally, with a flourish, whip out a handkerchief to try to contain the blast.

That handkerchief was one of the staples of my father’s wardrobe. He’d grown up in the 40’s and 50’s, when adults still wore hats to go into town and women dressed like Jackie O for an afternoon of bridge. Back then, it was common for young men to carry a handkerchief. Manners mattered, and sniffles, sneezes, or coughs were not meant to be shared with your neighbor. Also, if you happened to be a gentleman, it behooved you to have one on hand to offer a lady, should she cry in your presence (or, heaven forbid, because of it).

My father’s was a plain white cotton Fruit of the Loom variety, nothing fancy. I, of course, didn’t know him in the days before his fatherhood, so I can’t vouch for his use of it in wooing the fairer sex. As a father of five, however, uses for his handkerchief were endless. It became like Hogwarts’ Room of Requirement, materializing for whatever need arose, and there were many.

He used it for wiping toddlers’ tears and held it over our drippy noses, teaching us how to blow. He brandished it when we’d fall off a bike or out of a tree, a dampened corner dabbing at scrapes and scratches. It was handy for fishing: with fingers slippery from handling worms, a handkerchief in your grip helped remove a hook from the mouth of a crappie or bluegill. Once, when I stepped barefoot on a rusty nail protruding from a discarded board, the handkerchief staunched my blood en route to get a tetanus shot.

He worked his way through stacks of them. They started crisp and white, creased from the package, and by the time they were retired, they were marked with all manner of stains, likely riddled with holes, and sported more of a chalky gray hue. Stacked in a section of his sock drawer, they were arranged according to use: those decent enough for church, work, or more formal occasions, a used but not yet decrepit section, and then those on their way out, one oil change away from the trash bin.

I remember my father mowing the lawn on sweltering summer afternoons, pushing the old red mower in tidy rows back and forth across the St. Augustine grass. He’d pause every three or four passes and his right hand would whip a handkerchief out of his back pocket. He’d mop the sweat from his neck and face and soldier on. It would come out again when trimming the shrubs, leaning over a car engine, or painting a deck. Any outside activity was a surefire case for a handkerchief. If sawdust from a building project wasn’t generating that frightful sneeze, he could always use it to doctor the constant nicks and injuries from keeping a house and yard in tip-top shape.

If we ever found ourselves in want of a last-minute gift for a birthday or father’s day, the standby was a package of pressed handkerchiefs, monogrammed or plain, from the nearest men’s department. The shelves were always stocked full of them. I imagine they weren’t so much in demand as they once were in his day, times giving way to less practical things like silk pocket squares whose only use is to match a fancy necktie.

As I got older and moved out, I saw my father’s handkerchief less often, but in the days after my mother’s funeral, it was a constant presence. Home for that week, I’d look out behind the house to find my father walking out into the trees, a flash of white catching my eye as he hung his head and wiped his eyes, his grief a private thing with the woods his only audience. He’d straighten up and take a big breath before heading back towards the house, busy with people and casseroles, tucking his handkerchief back in its rightful place, no one, he thought, the wiser. What that simple piece of cloth must have witnessed, what depths of emotion it must have absorbed.

As the years passed, I’m certain he had more moments like those, hidden tears that come with the scourges of age: loss, worry, pain. The ultimate honor for a gentleman’s handkerchief, however, is not in service to self, but in offering aid to others. He used it to quickly catch a grandchild’s spit up and clean little fingers sticky from a popsicle. When collecting acorns or hickory nuts, it made a handy apron for a small child to carry treasures. It was ideal for wiping a damp golf cart seat to let a grandkid slide in beside him.

In the past couple of years, when I’d stop by his house to do my father’s laundry, I marveled at the number of handkerchiefs he still had. He’d been steadily giving away items for some time, downsizing to the essentials. His drawer still had unopened packages of new handkerchiefs. In his 80’s, he didn’t go through them as fast as he used to, fewer home projects, little grandkids all grown. Before his funeral, I raided my father’s handkerchief drawer. Each of his children and grandchildren, brothers, nieces, and nephews all held one during our last goodbyes. It seemed appropriate somehow, his last gentlemanly act of generosity for us all. Familiar with the fickle ways of grief, it felt to me he’d known how tears can arise at the oddest moments and had kept on hand the faithful squares to proffer.

I’ve kept that handkerchief nearby for the past seven months. I had it on hand a lot at first, like a security blanket, when bursting into tears at Costco, canceling a magazine subscription, or finding yet another piece of mail addressed to him in my mailbox. It definitely came in handy recently at my daughter’s graduation, my son’s wedding, and after receiving copies of my recently published book in the mail, all milestones I wish he’d been here to see.

This Father’s Day will be the first without my father, and I’m keeping his handkerchief in my pocket. You never know when a whiff of pepper might set you off, and I’m kind of partial to my eyeballs.

When Are You Going to Publish Your Book?

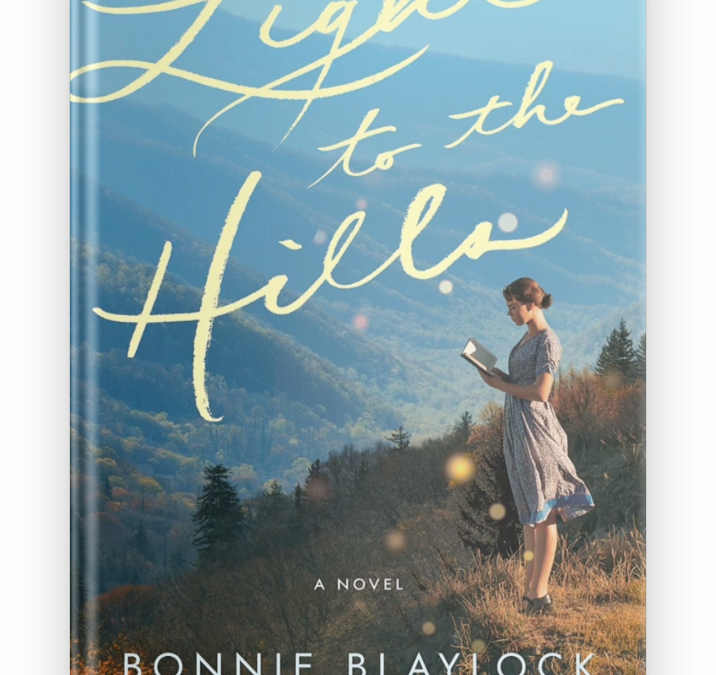

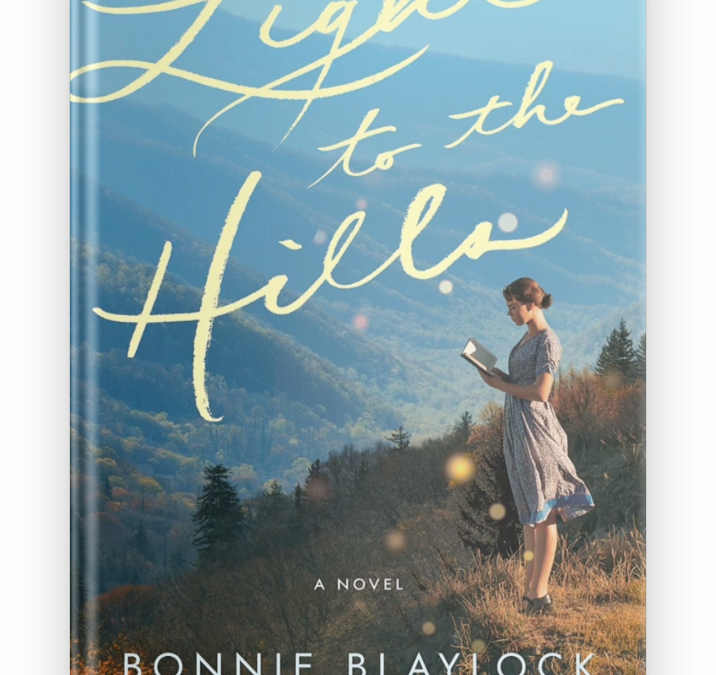

8 months. It’s 8 months until my debut novel is published and officially launched into the world. Less time than it takes to grow a baby but no less arduous. I should qualify what sort of baby. It takes a baby elephant almost two years to gestate, and this process has felt like elephant twins.

When you mention to people that you’re writing a book, or thinking of writing one, or even finished writing one, their response is usually something like “oh, cool, when’s it going to be published?” Generally, they have no clue this is an arrow to your heart, because if you could predict that bit of information, the whole writing-publishing-being an author gig would be a walk in the park. Mostly these folks are well-meaning and intend their question as encouragement, so it’s not their fault.

In 2014, when my firstborn left for college, I turned back to writing and began a blog, where I posted personal essays of humor and musings. After about a year of working those muscles, I started submitting to publications now and then, both online and print. Now and then, one would get picked up and published. Occasionally, one would get shared far & wide and surprise me, like the one about Marbles that seems to get recirculated every spring.

Two years later, when it was clear the second (and last) would soon leave, I began a novel. The reading and research that went into this paranormal thriller filled my time. If Dan Brown and Michael Chrichton had a baby, this would have been it: a fast-paced, high-stakes romp through history, art, and science. It took over a year to write. When I finally looked up from the keyboard, a little myopic and dizzy, I began asking questions. Now what? Who would read it?

I did some research and decided I didn’t want to go the self-publishing route. Although that’s a legitimate and growing option for many authors, as part of my education approximately 100 years ago, I’d attended Denver University’s Publishing Institute one amazing summer, and I’d always had it in my head that someday I’d try to get published “traditionally,” meaning my book would be picked up by one of the larger publishing houses. For most of these, authors can’t submit their work directly to editors. They must acquire an agent for their work to get past the gate. This would be my next step.

After poking around on Twitter and stalking the writing community and agent tweets, I discovered a new language. I learned about querying from The Query Shark. I learned what hashtags to pay attention to if I wanted to see what agents and publishers were looking for. I started my query list and began The Ask: the part where you send a letter to agents and ask if maybe, possibly, they would consider reading your book and helping you publish it. MOST of them passed. Some of them never even answered.

I attended a couple of writer conferences and paid a little extra to be able to pitch the story in person (you get 5 minutes, so make it snappy!) to agents who attended. I got a couple of requests for a partial manuscript after these, but they ultimately went nowhere. So much depends on what’s popular, what publishers are looking for–not for NOW but to round out their book lists two or more years in the future, and they weren’t feeling it.

Almost 18 months in, I moved on to a new story idea to take my mind off what felt like the reverberating silence of the universe. A new book. Historical fiction this time, set in 1930’s Appalachia, centered on two families who learn the power of words. A big departure from my first one with its international vibe. More reading, more research. Some “field trips” to get the background and setting right. Then, the discipline part: days, weeks, months of having my butt-in-chair for the hours required to generate words on the page. This is the decidedly unglamorous part. The part where distractions become overwhelming and the push to get to the next chapter can feel like the most grueling marathon, even though I loved these characters, the place, this story.

2018. Done. Now to craft the query, the synopsis, the pitch that might catch an agent’s eye. Once more, the query list, submissions, and lots and lots of waiting. This time, the stars aligned! Not only did this story garner interest and requests from the people I offered it to, I got the call. An agent loved it enough that she was willing to give her own time and energy to it in hawking it to editors and publishers she knew! What’s more, it turned out she lives maybe an hour away, though, totally gets the story and its sense of place, and I knew she’d be its champion.

That was that, right? It should be on bookshelves everywhere in a month or two, tops. Not quite.

We went back and forth with some rounds of suggestions and editing. Some agents will help with developmental edits like this, and some won’t. The goal of all of them is to polish the manuscript until it’s so shiny that the editor who finds it in their inbox simply can’t look away. This, for us, took another chunk of months. It was early 2019 when it went on submission in earnest. By this time, I’d begun a third novel to take my mind off the waiting.

Again, we got nibbles. Positive feedback and lovely compliments, but no one wanted to put a ring on it yet. Then, in the fall of 2019 a book was announced and my heart sank. An author named JoJo Moyes–(maybe you’ve heard of her?) published a book on the exact same subject! What were the odds??

My intrepid agent assured me it only meant there was interest in the subject and not to worry. Then a pandemic hit and publishing, like many other industries, got sideswiped. My agent kept submitting, and I kept not thinking about it (as if!). It wasn’t until early 2021 that we finally got another call, this time from a publisher who was also a fan of the story and wanted to turn it into a book. I can’t emphasize enough how not just any agent and not just any publisher will do. Authors really need to stick it out to find true advocates who resonate with the story.

So, that was that, right? It should be on bookshelves everywhere in a month or two, tops. Not quite.

Remember, I’d finished the book in 2018. Three years earlier. Now that I had a publishing contract, the book would go through additional stages of editing–some developmental editing, copy editing, and a final proof stage. In between, we’d exchange ideas about cover design, promo blurbs, and other marketing aspects that, while exciting, isn’t what most writers specialize in. Each stage brought the book one step closer to the light of day.

And here we are–in the spring of 2022–eight months from launch! For most publishing companies, once the book reaches that point, their job is done, and they’ve moved on to the other books for their lists one and two years out. I’m sure I’ll climb a whole new learning curve this fall, when, at the same time I’m putting words-on-page for the NEXT book, I’m also thinking about how to connect with readers and make “birth announcements” for the foundling that’s toddling around out there in the world. Just like when parents “author” a child, authoring a book and helping it do well and reach its potential is the real crucible.

Can’t wait for the world to meet the new baby!

The Great Unraveling

Here in the warm, fertile South, things grow. Our county fairs are famous for tomatoes, pumpkins, and melons of mammoth proportions. My grandma’s house in the Florida panhandle sported a sleeping porch that was all but taken over by philodendron vines that crept and spread, covering each wall. One night spent out there beneath the green ceiling and your subconscious would swim with humid jungle scenery, spurred by the nocturnal buzz and chirp of frogs and cicadas.

You’d think, surrounded by such constant, urgent growth, I’d be more attuned to change, that it would be less of a personal affront. And yet.

A few years ago, in the space of a few months, my oldest got married and moved out of state, my youngest launched and started college, my husband and I sold the business we’d run for 20+ years, we turned 50, and my elderly father moved nearby. Shortly after the dust settled, we found ourselves slow blinking at each other over coffee one morning. We’d reached our day of reckoning.

It’s been a solid two years of what I call The Great Unraveling.

When my son was young, he’d wake up in the night complaining that his legs ached. For weeks, he’d limp around the house, gingerly favoring this knee or that ankle. Growing pains, the pediatrician told us, and I’d laughed.

“Wait. That’s actually a thing?”

“Yep,” he’d assured me. “It’ll eventually stop. His insides are just stretching to keep up with his outsides.”

Sure enough, his pant size finally leveled out and I quit doling out a fortune for hardly worn jeans. He stopped at 6’2″, and it still startles me every time I have to crane my neck to look in the eyes of the young man I used to walk hand-in-hand with across parking lots.

In the Great Unraveling, it felt like that. Achy and unstable. We’d done too much all at once and our insides were not keeping up with the outside. All of it was what we’d worked toward and hoped for, yet we were as disoriented as if we’d leapt from a whirling merry-go-round, staggering around like drunks with arms akimbo. And, for the love, where were all these tears coming from, spilling forth unbidden from some infinite inner spring?

Lou Holtz, the Notre Dame football coach, is credited with saying if you’re not growing, you’re dying. Well, Lou, sometimes growing feels like you’re dying. Moving away from what’s known and comfortable to uncharted and untamed territory can trigger staggering grief. Even the ancient cartographers knew: there be dragons.

A curious emotional cauldron bubbled within, a witch’s brew of joy and excitement for my kids’ futures, and a deep and marrow-filling sorrow at their departure. The same was true for my own self: eager anticipation for how my marriage might deepen and grow, given the extra hours we’d have now that it was just us again, paired with the struggle of renegotiating roles, schedules, and what a given day might look like now that we shared the same work space, absent of children.

What was next for me? Now that my days were untethered from my kids’ schedules and needs, now that our professional and financial lives looked different, what might I discover, pursue, try? Quite a bit, it turns out. I wrote a novel, began a second, started mentoring younger families with kids and hosting a thriving group of newly married couples. I had plenty of time to read, write, think, and connect with others. I found lots more time for the garden, creativity, and plain old leisure, which I’d almost forgotten about.

Undertakings, you might call them, all these new activities. It’s a curious word since an undertaker is typically one who deals with the dead. I suppose that’s who I’d become, in this new space, mourning what had passed, offering comfort to who and what remained, and ushering in what was to come next.

“What’ve you been up to, mom?” I imagined my children asking.

“I’ve become an undertaker.”

“Okaayy. Is dad home?”

The only one who likes change is a wet baby, Mark Twain famously said. That’s true, while it’s happening. It’s on the other side of change where we find ourselves marveling at why it took us so long to get here in the first place. Who knew we’d love sushi? Or enjoy taking walks with a friend? Or actually settle into not having to know what the kids were doing or who they were with and could trust them to get the oil changed and get a haircut? Because they were changing, too, growing madly into new versions of themselves and shucking their childish skins like a heavy coat on a warm day.

I never would have thought, at first, that I’d be savoring this new, delicious way of being and discovering, just the way I’d relished the loud and busy days of before. Maybe it was the cynic or pessimist in me who’d questioned whether anything could match what we already had, who kept posing the question “what now?” in an irritable, can’t-be-bothered tone instead of an eager “what’s next?”

It occurred to me that just as the pediatrician used to mark my kids’ milestones and percentiles, I might measure my own growth this way. What can I do this year that I couldn’t six months ago? Am I trying something new? Conquering fear to take a brave risk? Bursting into tears less often? Baby steps.

Somewhere along the way, babies quit opening their mouths like trusting little birds when we aim the spoon their direction. They develop suspicion and guard against what they’ve learned might be yucky or what could be good but what’s probably strained peas. They turn their heads with clamped lips and refuse to try.

For a good part of the Great Unraveling, I turned my head and refused. I wasn’t about to get a mouthful of peas when what I wanted, what I yearned for was pears and ice cream. I was, in other words, a big baby. I pouted, sulked, withdrew, and cried. I moped, slouched, sighed, and frowned.

All the emotional turbines churned, and maybe there’s a place for that. Maybe we have to sit with that a minute (or a week or month or more) and bear witness to all the feelings that arise with gravity-shifting change. I observed all the big emotions as they unwound themselves and noticed them gently. I didn’t accuse, belittle, or dismiss any of them. Being unspooled is a vulnerable place to be, and vulnerability needs to be met with kindness, above all. Fellow travelers in the same boat are excellent companions for this, by the way.

But the unspooling leaves you with work to be done. It leaves you with a heap that must be rewound and reworked into something new. Made of some of the same material, no doubt, and colored with what came before, but an entirely different creation. Not pears and ice cream, but not exactly strained peas either.

Crossing these thresholds of the “what was” and “what’s next” requires some of the toughest growth there is. Our limbs and hearts ache with it as we resist, or at best, struggle to keep up. Liminal spaces like these are sacred, holy ground. They are where the unraveling occurs and where we discover what anchors us, what tethers remain, and what we’re capable of, still. The author and theologian Richard Rohr, warns us, despite the pain and discomfort, to find these sorts of spaces regularly. Actually seek them out on purpose. He urges us to “get there often and stay as long as you can by whatever means possible” because if we don’t find such thresholds in our lives, “we start idolizing normalcy.”

And, boy, if 2020 taught me anything, it was how much I was infatuated with normalcy. How, in the end, we’re all pretty much avoiding the peas and stomping our feet about the ice cream we’d expected.

I think perhaps, for me, this particular Great Unraveling is nearing an end, for now. As I spend time with my aging father, I can easily see others on the horizon, and I resolve to approach them with less resistance and more purpose next time around. The decades unfold and the only constant is, of course, change. We help one another over the thresholds, saying watch your step and, with a sweep of the arms, welcome, welcome.

Something to Behold

Last night on the winter solstice, literally the darkest day of 2020, my son and I craned our necks skyward on the front lawn.

“Can you see it?” I pointed. “Below the moon to the southwest.”

Just the day before, I’d sunk pretty low, feeling decidedly un-festive and weary of the yoke of fear, anxiety, and loss wrought by a year that seemed to present fresh disasters with the dawn of each new day.

As soon as the sun dipped below the horizon, the bright orbs of Jupiter and Saturn appeared. The distance between them is something like 500 million miles, but from where we stood, the planets seemed almost to collide amongst the stars above. People were calling it “The Christmas Star,” an occurrence unwitnessed for 800 years.

Having no telescope, my son and I glanced at each other once we’d spotted the planets. Had there not been such media fanfare, we would definitely not have noticed the sky that night. It was cold and dark, and the warm living room beckoned. It wasn’t the blinding flash of light I imagined the shepherds following to a humble stable in Bethlehem. Truth is, seen with the naked eye, it was a bit underwhelming.

And yet. As I stood peering into the darkness, a word kept coming to mind: behold.

What does that mean?

A funny little word, behold isn’t something most of us use every day. “Behold, I’m home!” “Behold, child, here is thy dinner lain before thee. Partake and be glad.” It’s clunky and archaic, but it carries a simple meaning: look and see. Pay attention.

In older translations of the Bible, behold was sprinkled through the pages over 1200 times, but as time passed, its use waned. A quick glance at my NIV concordance showed it was not important enough to be referenced, and modern translations like The Message show no uses of the word. Not even one.

Is this because so few things amaze us anymore or because, weary and numb, we’ve stopped paying attention? We’ve stopped beholding. It doesn’t occur to us to venture out and raise our eyes to the sky.

Half a miracle

A few verses in the gospel of Mark recount an odd little event where, in Bethsaida, Jesus is asked to heal a blind man. By this time, He’s fed the multitudes, walked on water, cast out demons, and raised the dead. One more blind man should have been a one-and-done sort of moment.

Instead, we read the only half-miracle recorded in scripture.

“When He had spit on the man’s eyes and put His hands on him, Jesus asked, “Do you see anything?” He looked up and said, “I see people; they look like trees walking around.” ( Mark 8:23–24, NIV)

People like trees? Had there been a miracle glitch? A power outage? Was restoring sight suddenly too hard for the Son of God?

Maybe it was like me and the Christmas star. I’d witnessed something amazing — enormous gaseous balls of rock suspended in the heavens, reflecting the moon’s light back to earth in a stellar array that won’t be seen again for another 80 years.

I saw them through eyes and a sense of sight perfectly tuned and designed, which in itself is an extraordinary feat of creation. There I stood, on legs that held me upright, breathing in the cold December air with no effort. Yet all I could muster was a nod before retreating to my spot on the couch.

Oh me of little faith

God is ever patient with us. He let me get comfortably settled before the text came through. A friend sent me a long-exposure photo of the event and bam! There it was. Now that could get a shepherd’s attention. That was something to behold. Of course, that’s what it had looked like the whole time, but I hadn’t seen it the way the camera caught it. Because it didn’t match my expectations, it was easy to dismiss and shelve as just another hopeless 2020 disappointment.

I love the next two words in verse 25. Once more. Jesus doesn’t scold or walk away in disgust. He doesn’t clench his fists in frustration over the man’s lack of faith or hard-headedness.

Instead of pinching the bridge of His nose and heaving a loud sigh at the blind man’s veiled recognition, once more, Jesus put his hands on the man’s eyes.

“Then his eyes were opened, his sight was restored, and he saw everything clearly.” ( Mark 8:25, NIV)

How often we, too, need an extra boost to see. How often we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror before grace reaches down to clear the mist clouding our vision. Behold. Look and see. Pay attention.

The fact that the longest, darkest night of the year coincided, this year, with the Christmas star can surely be taken as a sign for those who would pay attention to such things, a nudge of grace for a world that pines for a glimmer of hope.

It was just what I needed to lift my dark mood and remove the veil that had caused me, like the blind man, to see people like trees walking. My dimmed vision and the burdens of this difficult year had fooled me into believing things — including myself — were somehow less than.

All year I’ve had a sense that something important was happening, in and around me, but whatever it was has been kept curtained off. That evening, as I watched the lights on the tree twinkle like stars, lines from a familiar Christmas song played in my head:

A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices; For yonder breaks a new and glorious morn. (from “O, Holy Night”, Adolphe Adam)

As we celebrate the fortuitous advent of Emmanuel, may we be granted eyes to see — a 20/20 vision, if you will — the wonder that surrounds us, even still. The Light that leads us. The grace and hope that carry and sustain us. Fear not, the angels say. Behold.