Hand-Me-Downs

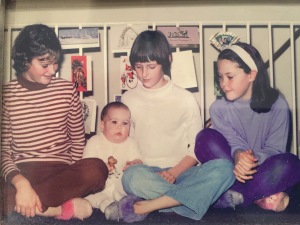

I am a fourth-born and a first-born. My parents had this great little family of 3 daughters, each two years apart. Then they waited 8 years and had me and my younger brother in quick succession. Though this technically ranks me fourth, the large gap made us kind of a split-level family, and I got the typical first-born personality while resting firmly in the middle of the pack.

This also meant that my older sisters had two different parents than my brother and I. Oh, they were the same mom and dad, but my sisters had them when they were young and fresh. My brother and I, as usual, got hand-me-downs. Parents worn out and frayed from years of use, whose eyes were not as vigilant, and whose determination to teach us certain skills was lagging. The older three always accuse my brother and me of having some sort of fantasy childhoods, with no supervision or required chores (but they’re not at all bitter).

Their tales of responsibilities and chores could be true. My “hand-me-down father” used to make me spend hours hand-trimming the St. Augustine grass under the chain-link in the backyard because the fence supposedly damaged the weed-eater’s trimmer line. I suspect this was less of a fact and more of an excuse to get me outside and building character. If this was an example of his lighter, more relaxed task-doling, then maybe they really were triple Cinderellas.

In my sisters’ childhoods, before my brother arrived as the family’s caboose, my father taught all three of them to play softball. My grandmother (his mom) scolded him, terrified he pitched way too fast. He argued that if he didn’t pitch fast and hard, they wouldn’t be motivated to catch the ball. When your options were to either catch it or get beaned by a 50 mph fast ball, you quickly developed good hand-eye coordination. All three of them played on girls’ softball leagues and could hit, field, and run like Geena Davis in A League of Their Own.

By the time I was old enough to have a go, the gloves were already broken in and soft. All but one sister had flown the nest, and either my father’s interest had waned or, more likely, a decade or more had passed and he was just more tired. He had already taught the sport three times and maybe he had run out of gumption to do it once more. I never caught a blazing softball and, as a result, was one of those picked last in junior high gym. In fact, I never played any team sport, and while my brother did, he didn’t stick with any of them for long. We each ended up preferring more solitary activities: him, fishing; me, riding horses.

My hand-me-down parents may have been worn out from repeatedly raising toddlers and teens, but they were also wiser. In his fascinating book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell explains how the magic number of becoming an expert at something is 10,000 hours of practice. If you go by the numbers, after just one year (8,760 hours) of parenting, you’re already almost a success. The catch, and there’s always a catch, is that right about the time you’re an expert on babies, they become toddlers and you’re back at ground zero. Then they hit kindergarten and everything changes. Dump some hormones and puberty in the mix, and just when you thought you were making progress, you go straight to jail, do not pass Go. Becoming an expert in parenting (if there even is such a thing) takes twenty times longer than any other skill because the target keeps moving. (Gladwell has no children, by the way.) Because they had so many of us, my parents had gone through these phases multiple times and were experts 10 times over by the time my brother and I arrived on the scene. Raising two more kids was like buttah.

If we didn’t change and grow as we age, if we parented all our children making the same rookie mistakes we made on our first-born darlings, it would be weird. I hope I’m not the same parent in my 40’s as I was in my 20’s! This morphing parent phenomenon is most obvious when your own parents become grandparents. Our jaws have dropped on more than one occasion when our parents have allowed our kids to do things that would have earned us a well-tanned hide. Remember the Abraham & Isaac story? Faithful Abraham dutifully prepared to sacrifice his teenage son. Show me the altar, he said. (They’d probably just been arguing about too much texting or getting the car keys to go the mall.) I’ve often said that if Isaac had been Abraham’s grandson, Abraham would have scooped him up and run like the wind, and Genesis would read very differently.

My husband and I discuss this in wonder. Who are these people? They are not the same people who raised us. And if they’re doing it right they shouldn’t be. The Skin Horse in the classic Velveteen Rabbit story explains how being loved by a child makes you more Real: “It doesn’t happen all at once. You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby.”

I appreciate my sisters blazing the trail with our parents. They got the handmade clothes, bad bangs, and strict curfews. It’s a mixed bag, though. The hand-me-down parents I got may have been more relaxed and financially better off, but no matter what my brother and I threw at them, it wasn’t their first rodeo, and they fielded our fastballs with ease. As younger siblings we did have the benefit of watching and learning from everybody else’s experiences. From my sisters we learned not to let dad catch you sit ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.

ting around watching TV when he got home from work, and the best time to ask mom for permission for something was when she was almost asleep in her chair.

When we compare childhood experiences, we marvel at how different they are. It’s not like they were in a gulag and we were raised by wolves, but to hear them tell it, well, almost. Thanks for limbering them up for us, guys. Way to take one for the team!