by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 25, 2016 | Thoughts

“I am a writer.” I said that out loud to a stranger earlier this year and immediately glanced around to see if the store’s security was hurrying forward. I must have been blushing because I felt my face get hot and my stomach somersaulting–kind of like being twitter-pated in the springtime. (It’s a Bambi reference. Go back and review your Disney films.)

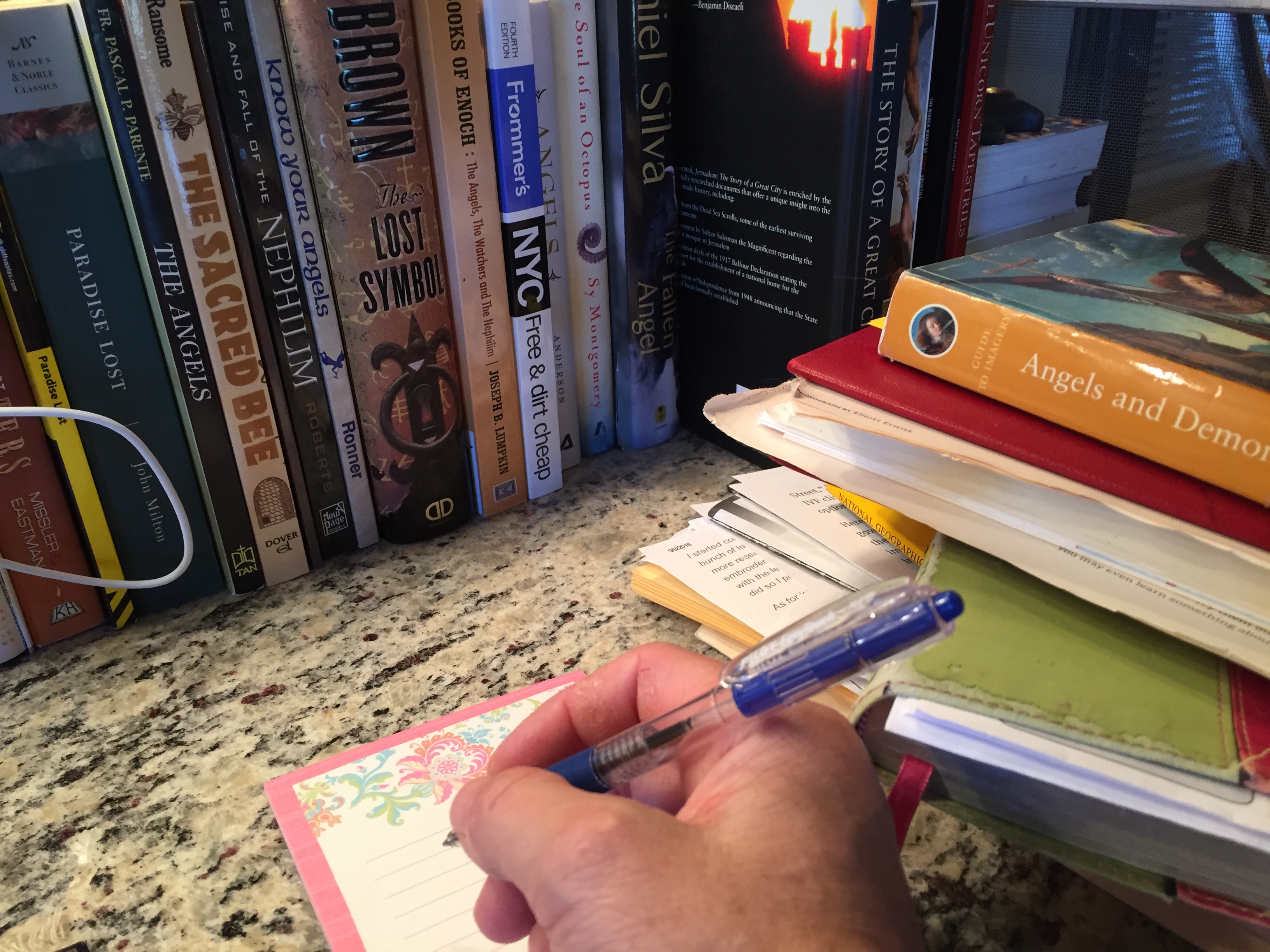

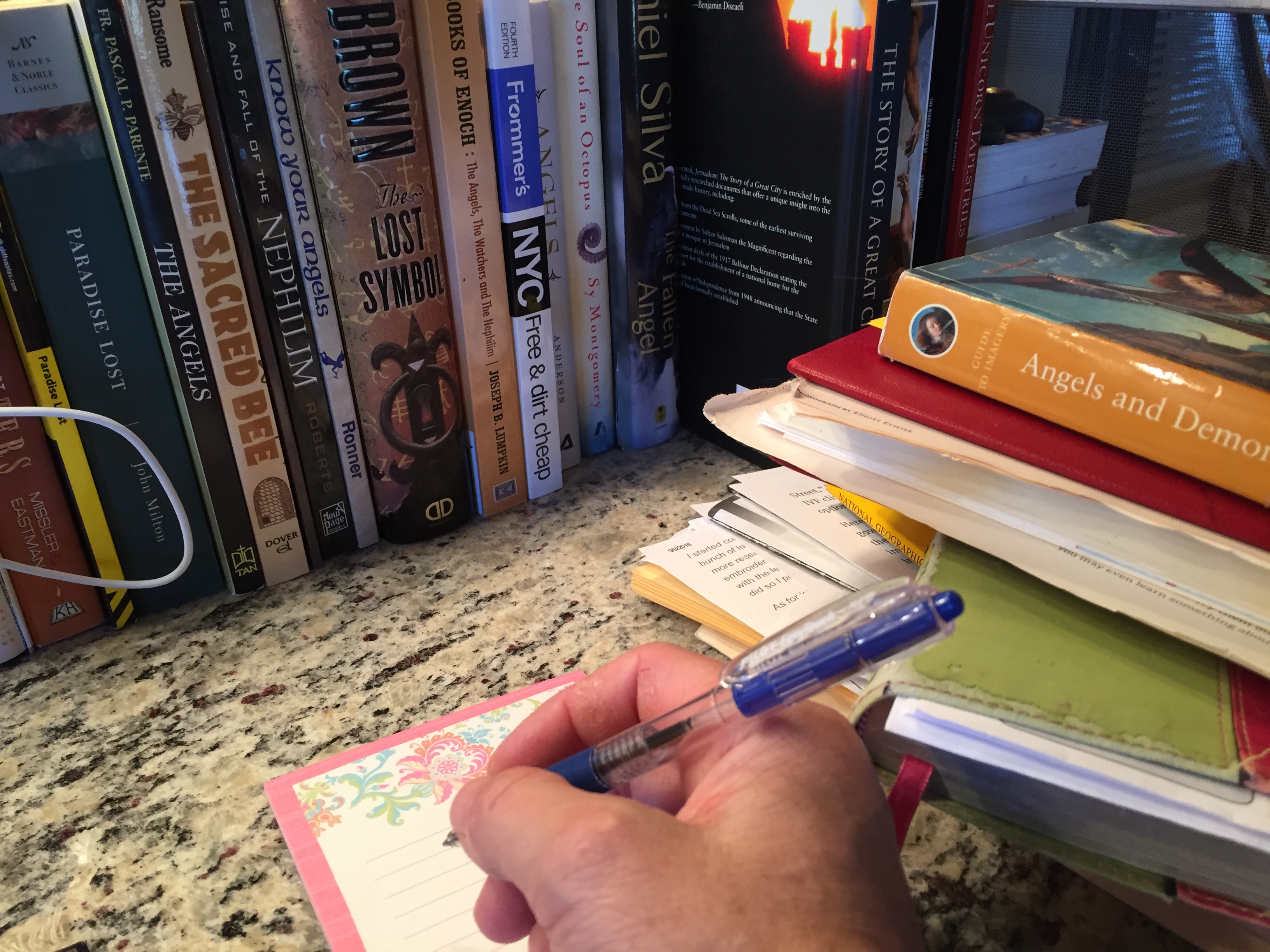

I felt like any second my subterfuge would be discovered. It wasn’t like I’d claimed to be a 300 lb black woman, a fraud people could instantly detect. Anybody can raise a hand to be counted as a writer and no one would ever know the truth. I was buying a ceramic octopus, intended to sit on my desk as inspiration for a YA story I was working on. The lady in line behind me asked what it was for, and before I could shrug it off as a silly knick-knack, the words just slipped out and there it was: now the universe knew.

I hadn’t really written since college, when I had deadlines to churn out short stories, screenplays, and for a while some truly awful poetry. Before that, since I can remember, I dreamed up tales for fun and was always in favor of essay tests instead of multiple choice in school. When the real world of work, family, and responsibilities closed in, I pushed writing to the back of the closet, pulling it out now and then to write silly Christmas poems for friends or edit other people’s writing.

All this was fine, I told myself, because you’re not a writer. Instead, I read constantly. Digesting a steady diet of words, craft, and imagery, whether I knew it or not, kept me tethered to possibility. Daily, the crowd of impish meanies in my head scoffed rudely and produced lists of reasons why I could not and should not try this at home. It doesn’t count if once upon a time your mama said you were good. If you dare crack open that door, you will be like the pathetic American Idol contestant who can’t carry a tune in a bucket but who imagines they are Barbra Streisand. A clown. A hack. A public joke. So fear got to be the boss of me and I reasoned that the world had plenty of amazing writers already. Exhibit A: my overflowing bookshelves.

Plus, I was too busy. A small business and growing family left no time for indulgences. I had “nothing to say.” Then my oldest left for college. I’m sure there’s an entire psychological avalanche of reasons why, but suddenly the excuses petered out. Now a couple of decades older, I had had experiences that perhaps did give me something to say. I no longer cared about the impish meanies. Why had I listened to their chorus in the first place?

So I started pecking out blog pieces, personal essays mostly, bits about my crazy family. There was no snickering, rotten tomatoes, or death threats. Turns out when you hit “publish” and your message in a bottle drifts on the universe’s currents, no one much sees it. Then I wrote a chapter based on an idea I had and made my teenage son listen to it. Every few days, I’d do another installment, our evening miniseries. Two more ideas later, I have another YA novel (the octopus) and a supernatural thriller in the works.

Each small step has led further down the path to connections, exposure and bravery. Lots and lots of bravery. It dawned on my that I preached to my kids about taking risks and pursuing their interests while I sat like a mouse huddled in a corner with what really mattered. My oldest went sky diving this year. Sitting at a keyboard and turning yourself inside-out across a page can be kind of like that. Every fiber screams that this is a really dumb idea and you should just back out, but then you hit publish and you’re airborne, sucking wind and trying not to die.

But the parachute! Once that sucker opens and you’re not hurtling towards earth, it’s kind of cool up there. The view is fantastic. Your fellow jumpers are all giving you the thumbs up with goofy grins plastered across their faces. Floating like that releases a feeling of freedom and rush of endorphin because you know you’re doing exactly what you’re supposed to be doing.

The community I’ve discovered on Twitter and Medium, the blog followers and Facebook commenters are the lift that enables flight. Julie Valerie’s monthly blog hop has been both a motivator and an inspiration. So many resources are available today that weren’t when I was literally typing out drafts on a manual typewriter all those years ago. In this next year, I plan to participate for the first time in NaNoWriMo to force me to complete one of the half-drafts filed on my desk. I will continue to submit beyond the blog to other outlets and contests. Next fall, because I plan to guard my work time more jealously, I will enter PitchWars. Because, curse you, impish meanies: Why Not?!

And because, like I told the octopus lady in the store, I’m a writer.

Thanks for reading! To return to the FICTION WRITERS BLOG HOP on Julie Valerie’s website, click here: http://www.julievalerie.com/fiction-writers-blog-hop-oct-2016

by bsquared5@aol.com | Jun 28, 2016 | Thoughts

**This post originally appeared as a guest post on The Eternal Scribbler.**

Anyone who has ever wanted “to be a writer” knows that putting coherent thoughts on a page can be a challenge. So many elements vie for a writer’s attention: setting, plot, word choice, character, dialogue. Trying to tame these wild things into submission sometimes feels like a frenzied game of Whack-a-Mole, flailing away in a sweat ending only with the writer needing a stiff drink and the mole hobbling about with painful bruises.

On any given day, writers tend to waver alarmingly between feeling god-like and feeling like something scraped off the bottom of a pig farmer’s boot. One minute, characters and ideas spring like gazelles from their imaginations, and they spin gripping tales of romance and danger they can’t wait to share with the world—or at least that one friend who only says nice things. In the space of an hour, their mood shifts–now dialogue reads like it’s been recorded by the minivan navigation system and all the characters are dull cretins who move stiffly through the plot like hand puppets.

The difference between the first—(the artist)—and the second—(the hack)—lies in writing invisibly. Many years ago, pushed by a looming deadline in a graduate class, I wrote the following story, hoping to at least win some humor points with my professor. This is one version of “invisible writing.” Bonus: it takes less than a minute to read.

The Invisible Story

Once , prince princess.

marry, but

evil dragon. ?

“No!”

“ , my love.”

many tears.

land far away, .

, . !

Instead, her. “ !”

roaring, gnashing, flaming .

scales . Sir .

princess. , thrusting his sword, .

, ! last gasp,

shattered armor . roar,

triumphed, eating . grisly .

died of grief

from her tower.

Moral:

While the moral of this story is left to the reader’s imagination, you easily garner the main idea with just fragments and punctuation. The thing is, it takes very little to convey an entire plot. The skeleton of a story, if it has strong bones and especially if it’s a universal tale or truth that resonates, can ably stand without much interference from an egotistical writer.

Writing that appears effortless tends to occur when the writer gets out of the way of the characters and their goals. The writer is present, of course. The story and voice are hers, but she doesn’t leave grubby fingerprints all over the pages, which is distracting at best and annoying at worst. Rather than keeping a white-knuckled grip on the wheel, a good writer lets the story steer itself for the most part, with only the slightest corrections here and there. I love that the earliest writing tools were quill pens topped with feathers, a visual reminder to have a light touch.

How do you write invisibly, less heavy handedly? There’s no need to be as cheeky as my example.

- Know the tools. Grammar, spelling, punctuation, sentence construction. Read anything by William Zinsser or go back to your high school Harbrace for the basics. This should go without saying, but here I am saying it. Leaving errors littered through your writing is leaving a trail of breadcrumbs straight to the writer rather than allowing the reader to focus on the story and is anything but subtle.

- Write YOUR story. This does not mean that if you have never touched a dragon, you can’t possibly write about them. Imagination is allowed! It simply means that the truest (most invisible/effortless) writing that will resonate most with others is that bit of yourself that has been scarred, deliriously happy, or terrified. Draw upon that instead of manufacturing fake tears—the reader can tell. Everyone has her own story. Even if everyone has been to a sixth grade dance, not everyone has been YOU going to YOUR sixth grade dance.

- Pay attention to language. If you don’t have a somewhat freakish fetish about words, back away slowly from the page. Writers should at least feign interest in the words they enlist. Otherwise, the workers may just rise up in mutiny. Thesauruses are useful, but use real, recognizable words. Don’t use a fifty-cent word when a nickel word will do. Don’t insult the reader’s intelligence by explaining everything in excruciating detail. Some writers are like those people who shout rudely at foreigners, thinking they’ll be understood better if they just increase their volume. Finally, use profanity sparingly. As my mother used to say, it shows a lack of imagination.

- Practice. Lots. It takes at least 10,000 hours to be any good at anything, so you may as well get comfortable. In the course of practicing, in which you will write choppy, painful sentences and incoherent drivel, you will eventually learn to sift the chaff from the wheat and begin to duplicate the parts that flow, have a rhythm, and ring true—in other words, parts where you were invisible and the story shone through.

- Imitate. (see #3). In your love affair with words, you will need to read prolifically, maniacally even. Read widely and outside your preference and culture. Read poetry, screenplays, non-fiction, and novels. Reading will do two things: it will increase your vocabulary and it will train you to recognize beautiful craft. At some point, you will be casually reading a paragraph or a sentence, when you will be struck by its perfection. Not only has the writer nailed a feeling or situation so exactly, but he will have done it with words that read like poetry, where your only response is to pause, savoring it and staring into space at the deliciousness of it, the book held limply in your lap. That is what all writers aim for. Find your writing heroes and reverse engineer them. Let them influence your thinking, which will influence your writing.

You will still have those distracted Whack-A-Mole days that leave you exhausted from the wrestling match, but try to tiptoe more than you stomp through your pages. Your readers will appreciate being beckoned softly along by the voice of the invisible writer.

by bsquared5@aol.com | Oct 25, 2015 | Thoughts

One of my nieces was once so pleased with herself for learning to write her name that she found a rock that fit nicely into her kindergarten-sized hand and scratched out all five letters. Onto the side of my sister’s new van. She even neatly scribbled out one of the letters and corrected it.

After the hell fire and brimstone rained down, she wrote it repeatedly on more appropriate surfaces. Writing, it seemed, was a delightful new skill.

Holding my son’s hand the other day, I realized he was missing something: a writer’s callus. Incredulous, I quizzed his sister and some friends of hers.

“A writer’s what?” they wanted to know.

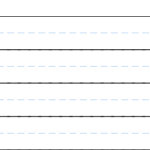

“You know,” I explained, showing them my right hand, “that bump on the side of your finger where the pen rests. It’s that raised rough spot you get from writing. Like, from taking notes and writing essays.”

The smooth-fingered youths had no idea what I was talking about. My oldest was in third grade a decade ago. That is typically the grade where children are taught cursive writing. That year, they grudgingly made it through about half the alphabet before moving on to another topic. The year after that, the school stopped teaching handwriting altogether. Ask my younger child to sign his name and it’s different each time, a flat squiggled imitation of what he’s observed from his father and me. They write all their work on their laptops and email it in to the teachers. Taking notes in class is sometimes a simple matter of taking a picture of the board with their phones.

I remember spending hours–hours–practicing handwriting on page after page of paper  that looked like miniature roads running from left to right, a dotted center line between two solid lines, the guide for how high each lower-case letter should reach. We were graded on penmanship, required to write our letters to Santa this way, and the requisite post-Christmas thank you notes to far away aunts and uncles. By the time I reached middle school, I could chat with my latest crush and execute countless finely doodled “Mrs. Stephen Bishops**” on the pad by the telephone, wrapped in its spiraled cord. (**Names have been changed to protect said no-good, cheating twerp and my less than stellar character judgement.)

that looked like miniature roads running from left to right, a dotted center line between two solid lines, the guide for how high each lower-case letter should reach. We were graded on penmanship, required to write our letters to Santa this way, and the requisite post-Christmas thank you notes to far away aunts and uncles. By the time I reached middle school, I could chat with my latest crush and execute countless finely doodled “Mrs. Stephen Bishops**” on the pad by the telephone, wrapped in its spiraled cord. (**Names have been changed to protect said no-good, cheating twerp and my less than stellar character judgement.)

When my family moved just before high school, I spent mopey, sulky days writing long letters back “home” to my friends, pages of thoughts, drawings, and stories that grew so bulky the envelopes required reinforcing tape and lots of extra postage. I filled journals, amusing to pull out and read now, my teenage angst leaping from each page, but instructive, now that I am raising teenagers, in remembering what it was like, inhabiting that lonesome territory.

In high school and college, my note-taking was fast and furious, letters small and sure. Small handwriting is supposedly a sign of introversion and an ability to concentrate, in my case probably accurate. Once, for a chemistry test, a teacher cleverly allowed us to bring a “cheat sheet” to class, with a catch: it could only be one inch square. While I am not so focused as to fit entire book chapters on rice grains, like artist Trong G. Nguyen, I managed to fit every chemistry formula I needed on that tiny square. I wrote countless papers and my master’s thesis by hand, typing and retyping it in final draft on an electric typewriter, halfway high on White-Out correction fluid. For graduation gifts, I received several Cross pens, some engraved, which the givers I’m sure imagined would be useful for decades.

I had a meeting the other day with a fellow writer, a guy in his mid-thirties. Curious, I asked if he had a writer’s callus. “No,” he shrugged. “I never even carry a pen.” He quickly transitioned from laptop to ipad to smartphone, typing notes, reading emails, and sending texts. Yesterday’s writer’s callus has morphed into alarming maladies of today: something called “text claw” and thumb arthritis.

Obviously, I have upgraded from my old electric typewriter to a computer. I have a smartphone and I know that an emoji is not a Japanese manga character. Although my teenage son frequently can not believe that I don’t use Siri and the fine points of Apple navigation are lost on me, at least I’m ahead of my father, whose idea of a text message is to send me an email with just the subject line.

Perhaps we have lost something in the rush of progress. I love looking at my husband’s grandfather’s Bible, with his shaky notes written in the margins. I treasure my mother’s handwritten recipes so much that I have one framed on my kitchen counter. At some point, she thought to organize everything and threw most of them away in favor of typed-out note cards. This is why I just cannot, will not, refuse to get on board with the Nooks and Kindles and handheld Bible Apps. Traitorous devices! Electronic highlighting and note taking is not the same as pulling a book from the shelf and happening upon a marginal note I’d written long ago, the handwriting and thinking a reflection of whatever age I was at the time.

A couple of my friends occasionally take the time to write notes. With a pen. On real stationery. It says something more than an email or text. Taking an extra minute to collect a thought or two, commit them to paper, and drop them in an actual mailbox may be a relic from the past, but what a joy to receive it amid the impersonal bills, catalogs, and the usual computer-generated fare. Maybe it’s another one of those genteel Southern graces like handkerchiefs or making a medicinal hot toddy.

I’m afraid someday my grandkids will be texting at Christmas time: Sup, Snta. How ru? Im gud. Pls bring prsnts!

I shudder to think. Until then, I just know I’m mourning the writer’s callus.